Dossier Acta Litt&Arts : La traduction du savoir et ses méthodes

Playing Medieval: Learning through Performance in the Alps

Texte intégral

-

1 The outputs of Jeu médiéval are translations/adaptations of French Medieval...

1The Spectacle of the Other is an on-going collaborative research project launched in 2015 by the Universities of Tohoku and Grenoble Alps. It studies the cultural transfers historically induced by the Performing Arts between France and Japan. More generally, it analyses the long process of East-West dialog through Arts, Literature, Languages and Human Sciences, and the current impact of these circulations on our globalized culture. Playing Medieval (Jeu médiéval), the training program I have created the same year, is part of this project, while included in the Learning-through-Performance program recently implemented at the University of Grenoble Alps1.

-

2 In this volume, Fukai Yosuke presents his innovative program developed for ...

2Playing Medieval’s general objective is to promote active learning in and through the Performing Arts. Different from other Learning-through-Performance programs enhancing active learning of a foreign language2, Playing Medieval aims to help Francophone students to regain access to their artistic heritage in recreating Medieval plays originally written in Ancient and Middle French.

3I will first sketch out briefly the reasons why accessing a past theatrical heritage can be difficult for students who aspire to become professional stage artists. I will then present the pedagogical specificities of Playing Medieval and some results we have achieved for few years.

Accessing past theatrical cultures: a difficult path

-

3 The PAC classes (classes à Projet Artistique et Culturel, classes with an A...

4For the last decades, academic curricula in the Performing Arts are blooming in French universities. They welcome thousands of students all over the country not only because performances and films are fashionable, but because France has developed for forty years a national program in high schools, unique in Europe, to give a pre-professional training in Performance and Cinema to selected pupils. In the PAC and CHAT classes, teachers and artists collaborate and practice intensively film-making and acting with the pupils (usually several hours per week during three years)3.

-

4 Since I experienced them myself, the following examples are chosen among th...

5The students who wish to develop further their skills at an academic level must however confront themselves to subjects often new to them. Among the theoretical subjects they have to study during their training in the Performing Arts, they discover the history of Western Drama from the Antiquity to the most recent creations. As a Medievalist, I was in charge of teaching French Medieval Theater (12th-16th centuries) to Grenoble first-year students in Performance Studies4. I soon realised that this subject was, for many reasons, a difficult one for them.

6The first obstacle is cultural. Though curious and motivated, students are usually not convinced that studying past forms of theatre is useful to someone who aspires to be an actor or a stage director in the 21rst century. Indeed, the most powerful principle in Western theatrical culture is originality. Professional artists usually claim to be innovators; new ways of staging are praised; brand-new plays and contemporary authors are most valued. Of course, the students know very well the importance of classics. In secondary school, they became familiar with Molière, Racine, Shakespeare; they have read their texts and performed their plays. But, and that is a second cultural obstacle linked to our school culture, the masterpieces of Medieval Drama – the Play of Adam, the first play preserved in vernacular language in Europe (mid-12th c.), the famous Farce of Pathelin (15th c.), among others – are not regarded in France as classics, the French ‘classical age’ beginning in the 17th century. Medieval plays are therefore not studied at school, and quite never staged in professional theatres. This is a paradox, considering that Francophone Drama was the most important theatrical tradition in Medieval Europe, in quantity and in diversity. Hundreds of plays have been preserved, from short comic farces to long ritual mystery plays, from political spectacles to satirical happenings. Numerous archives and documents inform about the staging, the actors, the audiences, the material context of the spectacles, etc. Despite its richness, this heritage remains a lost continent and first-year students in Theatre Studies do not feel the urge to explore it.

7A second obstacle is linguistic. Medieval plays are written in Ancient and Middle French, a historical state of French language that native speakers are not able to understand spontaneously. A translation is necessary. But what does mean ‘translating theatre’? To my view, when a play is translated, translation consists not only in a transfer of words from a text to another text. It also deals with body language, gesture, space and contexts of interpretation. Playing Medieval acts as incentive to learn how to translate through Performance and, in doing so, how to address the questions of recontextualisation and of re-enactment.

-

5 Les Conards de Grenoble, Ami et Amile, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-gr...

8A scientific re-enactment of Medieval Drama requires to fully grasp the historical conditions of production and of dissemination of the original plays. Here lies the third difficulty. Medieval Theatre is often strange to young people because it bares the cultural specificities of the past societies in which it flourished. Brought up in a country fully secularised, French students sometimes feel uneasy when confronted to religious references (i.e., for Medieval Drama, Christian references). They are prone to keep a distance with the values of the spiritual plays they study. For example, when a team of Playing Medieval 2015 chose to stage the Virgin Mary who helps the heroes in the 15th century epic play Ami and Amile, they gave the character a funny dimension of self-mockery. Mary appeared not in Heaven where she should have been if an exact reconstitution of the medieval staging was intended, but carried by a prop man and waving like a bird5. Another group changed radically the role of Mary in Rutebeuf’s Miracle of Theophile. Instead of saving Theophile from the claws of the devil, as it happens in the 13th century play, Mary refused to intervene in our time, where people believe more in economical success than in moral values.

Image 1 / légende

Image 1 / légende

Is it a bird ? The Virgin Mary appears on the shoulders of a prop man, Ami et Amile by the company Les Conards de Grenoble, March 2015.

Playing Medieval : objectives, organisation, outputs

9Launched in 2015 and taught every year since then by different assistants or associate professors in Theatre Studies, the Playing Medieval project was originally created for first-years students in Performance Studies, which explains some of its pedagogical objectives.

10These students, accustomed to active learning since high school and likely to become actors or stage/film directors, love to play and to experiment practical research on stage. The program is explicitly designed to allow them to test and increase their technical skills in acting and film-making. On the other hand, they are often reluctant to a more theoretical approach. Some have difficulties to memorise the numerous historical information they must learn about Medieval Drama. Many find hard to focus on precise scientific tasks – such as translating and rewriting the plays, explaining their semantic and practical difficulties, investigating their historical contexts – that they have never experienced before. Playing Medieval helps them to articulate their new academic book-knowledge with artistic creation. To succeed, the applicants must follow precise rules and respect a strict timetable. Each team has only a month to prepare a spectacle and to shoot a short film before the public presentation.

11A second objective is to reinforce the ability to work as a team. Due to the success of Performance Studies in French universities and to the absence of selection to apply for this curriculum, the classes of the first-years students are often crowded. In this situation, they find hard to work together. Playing Medieval encourages them to form small groups, called the ‘companies’, and to collaborate in a spirit of complicity and of playful competition. Each year, around one hundred and fifty students in Performance Studies are enrolled in the program. They form ‘companies’ of five or six actors, inspired by the Medieval theatrical companies and named after French Medieval authors and plays. All the companies are registered on the digital workspace dedicated to the project each year, where, during the working session, translations, notes, and short films are posted. The website includes a forum for debate open to everyone who wishes to comment on the on-going work.

12The working process follows several stages, monitored by the teacher. At a theoretical level, some lectures explain to the students the social conditions of production and dissemination of theatre in Medieval societies. More specific classes are taught about the plays, their aesthetics, their original staging, their modern recreations. Selected abstracts of significant Medieval plays (12th-16th centuries) are read aloud and their linguistic difficulties explained.

-

6 Company Gréban, La Passion d’Arnoul Gréban, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01...

13After this introduction, the companies should take the lead and work independently. Each group chooses an abstract of a Medieval play and rewrites it. The rewriting may be a translation from Ancient to Modern French. Some students like to work on the original text and to highlight some of its main peculiarities. For example, in 2015, the company Gréban was intrigued by the character of God who opens the renowned Passion play written by Arnoul Greban in 14506. How to stage such a character? Will God speak to us today in our everyday language, as it happened in the 15th century play? To address this issue, the company chose to let God speak off stage in Middle French, his voice coming from the sky as if the character speaks to us from the past. Others experiment adaptation. The characters, the topics and some of the original sentences of the play are kept, but a new scenario and a new text are created. If this possibility is chosen, the rewriting must be posted on the website and the principles of its adaptation clearly explained.

-

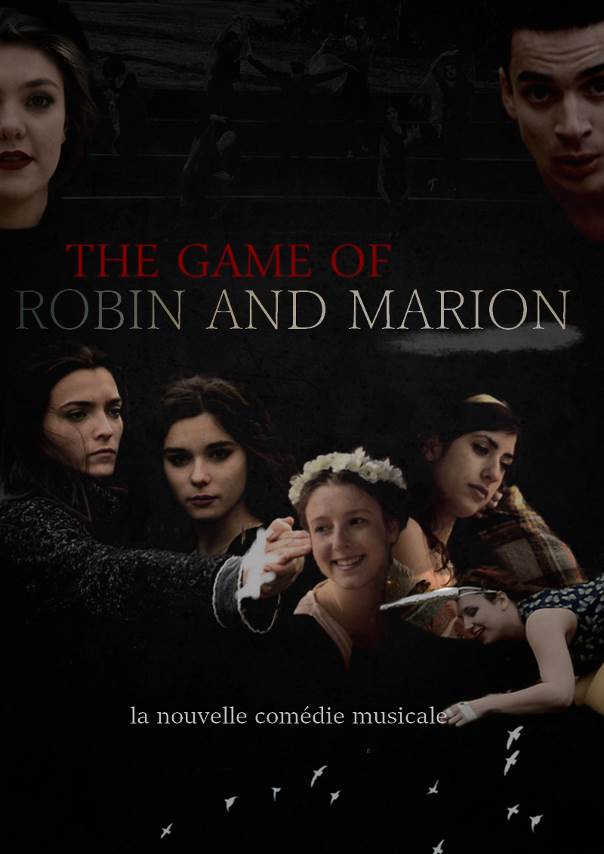

7 Company Jazme Oliou, Robin et Marion, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-gre...

14Then comes the time of the staging, which consists in two parts: a theatrical performance and the creation of a short film. Each group chooses a specific genre of short films: a recording of the performance, a trailer, an epic, a musical, etc. Each year, several companies are seduced by the first European musical play kept in vernacular language, The Play of Robin and Marion by Adam de la Halle (13th century). They enjoy adapting it to the standards of musical films today. This part of the work is very important because it motivates the students to reflect on their own visual culture. Adapting Robin and Marion into an Hollywood-style trailer for teenager movie, as the company Jazme Oliou brilliantly did in 20157, is a way to question commonplaces of such films: the naive song of the young woman in love, the threat of the (black-dressed) seducer, the dances in the nature, etc.

Image 2 /légende

Image 2 /légende

A Musical play for all times: ‘The Game of Robin and Marion’, a trailer created by the Jazme Oliou Compagny, poster of the movie, March 2015.

-

8 Company Antoine Chevalet, Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde, Jeu médiéval 20...

15The companies select the decors, design the costumes, find the useful accessories for their staging – some students even rode real horses to perform Arthurian knights8! They are expected to choose carefully the location of their performance. It has to be significant for their artistic project since in the Middle Ages, spectacles were performed not in specific buildings called theatres but in urban meaningful places. It is sometimes possible for the urban historians to precise the streets and places where the plays were performed during the Middle Ages; this is the case in Grenoble as in many French cities. The students are very sensitive to this local aspect because it creates a strong feeling of filiation between their work and the medieval performances that used to be located in their own town. When I launched Playing Medieval, I included one 16th c. play from Grenoble, The Mystery play of saint Christopher in a range of twenty-five plays to be translated and recreated. This particular play immediately attracted attention. A third of the companies competing that year restaged it or chose to name themselves after its playwright, master Chevalet. Thanks to local archives, we know that Saint Christopher was performed at the beginning of the 16th century on a large public place where Grenoble Museum of Arts is now built. This interesting coincidence inspires many questions to our participants: what does that mean to re-enact a spectacle at its exact location five hundreds years after its first performance? Do the young actors wish to preserve Medieval plays as if they were curators of a museum, or do they aspire to recreate them as if they were modern works of art?

16Indeed, a crucial objective of Playing Medieval is to motivate the students to explore the transfers between past and present. Such transfers have different dimensions: increasing our historical knowledge; translating and reviving our artistic heritage; reflecting on political and social issues of our time.

-

9 Company Maître Mouche, Farce du Mystère de Saint Christophe, Jeu médiéval 2...

17To conclude and invite to further discussion, allow me to give an example of this last dimension. In the Saint Christopher performed in Grenoble in the 16th century is included a farcesque interlude. Its plot is renowned for its originality: a theatrical company comes to entertain the court of Syria and the future saint Christopher is invited to watch the show in Damascus. Unfortunately, the actors have very little talent and the spectators refuse to pay them. Hoping to make money anyway, the stage director tries to sell some images of obscene catholic saints to the reluctant audience. The farcesque interlude was recreated in the streets of Grenoble in February 2015 by the company Maître Mouche9. But, instead of selling to pedestrians fake cartoons as described in the Medieval play, the actors acted as if they sold Charlie Hebdo. It was a month after the attack against the newspaper, when Islamic terrorists massacred several famous French cartoonists. In such a context, the recreation of a 16th farce dealing with satire, blasphemy, and comedy caught the public’s attention. People stopped, asked the students about their project and even participated to the performance in filming them. Thanks to this re-enactment, Grenoble inhabitants experienced an unexpected transfer of knowledge through time and space: the pedestrians watch the student company as if they were themselves the fictional audience of Damascus that is staged in the play, or as if they were the French spectators of the 16th century enjoying a good farce; they dialog with the students as citizens concerned by social and cultural issues of the 21rst century. That cold day, an academic training has briefly transformed into a political happening.

Image 3 / légende

An actor’s company and its (fake) audience: the farcesque interlude of the Mystery of Saint Christopher by Maître Mouche, Grenoble, March 2015.

Notes

1 The outputs of Jeu médiéval are translations/adaptations of French Medieval plays, records of the staging, sketchs of the costumes, videos created by the students, etc. They are available on the digital workspaces provided by the University of Grenoble Alps.

2 In this volume, Fukai Yosuke presents his innovative program developed for Japanese students who learn French.

3 The PAC classes (classes à Projet Artistique et Culturel, classes with an Artistic and Cultural Project) and the CHAT classes (classes à horaire aménagé théâtre, classes with a special schedule reserved for theatre) are the main curricula offered in French secondary schools to applicants who wish to train with teachers and professional artists. As any other curriculum, their results (theoretical essays and artistic creations) are measured by the baccalauréat.

4 Since I experienced them myself, the following examples are chosen among the achievements of the first program launched in 2015 [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/]. Creations have been realised and published under the supervision of my colleagues Shanshan Lü and Mathieu Ferrand every year since then.

5 Les Conards de Grenoble, Ami et Amile, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/mode-demploi-de-la-plateforme/travaux-xive-siecle-ami-et-amile-troupe-les-conards-de-grenoble/].

6 Company Gréban, La Passion d’Arnoul Gréban, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/mode-demploi-de-la-plateforme/xve-siecle-greban-mystere-de-la-passion-troupe-greban/].

7 Company Jazme Oliou, Robin et Marion, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/mode-demploi-de-la-plateforme/xiiie-siecle-adam-de-la-halle-robin-et-marion-troupe-jazme-oliou/].

8 Company Antoine Chevalet, Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde, Jeu médiéval 2015 [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/mode-demploi-de-la-plateforme/xiiie-siecle-les-chevaliers-de-la-table-ronde-troupe-antoine-chevalet/]. Victoria Rezelman embodies Lancelot riding a horse.

9 Company Maître Mouche, Farce du Mystère de Saint Christophe, Jeu médiéval 2015, [http://dip01.u-grenoble3.fr/wordpress/jeumed/mode-demploi-de-la-plateforme/xvie-siecle-chevalet-la-vie-de-saint-christophe-troupe-maitre-mouche-2/].

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Estelle Doudet

Université Grenoble Alpes / Université de Lausanne

Institut universitaire de France