Epopée, Recueil Ouvert : Section 2. L'épopée, problèmes de définition I - Traits et caractéristiques

History, Politics and Wars in Croatian Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Epic : An Overview

Résumé

L’histoire, la politique et la guerre sont les trois thèmes majeurs qui s’entrecroisent dans les épopées de la première modernité. On examine ici leur articulation dans huit longs textes épiques croates (deux datant du XVIe, et huit du XVIIe et des premières années du XVIIIe siècle), en prêtant une attention particulière à leur relation à l’épopée classique (sur le modèle de Virgile, médié par le Tasse), au degré d’émancipation du politique vis-à-vis de la morale chrétienne, aux valeurs véhiculées par les textes, et aux fonctions qui ont été la leur en leur temps.

Abstract

History, politics, and war are three interrelated themes of early modern epics. This article analyzes their articulation in eight longer Croatian epic texts, two of which were written in the sixteenth and six in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Special attention is paid to the relationship to the classical epic tradition (Virgilian, i.e. Tassian), to the degree of emancipation of the political theme from Christian morality, to the inscribed identification value statements and to the (social) functions of the analyzed epic texts.

Texte intégral

Introductory remarks

1Some context may be of help to readers who may not be experts of the South Slavic literatures and cultures, before delving in an overview of the Croatian sixteenth- and seventeenth-century epic literature.

2The national attribute in the term ‘Croatian sixteenth- and seventeenth-century epic/literature’ is used here anachronistically, i.e. from a modern perspective. In the imagery of historical contemporaries, the notion of Croatia/Croats did not have the meaning it has held since the second half of the 19th century. Modern literary historiography defines the situation of the early modern literature in the Croatian lands – again from a somewhat anachronistic perspective but not without certain political and identity grounds – as literary regionalism. During the early modern period the area of today’s Croatia was divided between three imperial powers : the Habsburg Monarchy, the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire. In the official national historical narrative only the central part of the area under Habsburg rule – which retained the Croatian name, both as a toponym and as an ethnonym, and some traditional institutions of local government, for example the title of ban of Croatia – is considered an “unconquered” land, a kind of historical bridge between the medieval Croatian state and the modern Croatian nation. But this area – extended roughly from the coastal town of Senj via Karlovac to Zagreb and Varaždin in the North – which in historiography is usually called Banal Croatia (or Kingdom of Croatia), was by no means the center of cultural and literary life in the early modern period. This status was held by the literature from Dubrovnik, a city-republic with broad internal political, economic and cultural autonomy, but under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire. Admittedly, in the 16th century, the neighboring literature of Venetian Dalmatia was able to compete with the prolific literature in Dubrovnik, but in the next two centuries Dubrovnik literature became more and more a model worthy of imitation for Dalmatian writers, especially in the field of literary language. After the Great Turkish War (1683–1699) and the Habsburg reconquest of Hungary another “literary region” emerged in Slavonia (the eastern part of present-day Croatia). These four parts of early modern Croatian literature differed in literary idioms and to some extent in orthography ; each of them functioned as a cultural entity with some features of group identity. Nevertheless, the borders between them were permeable, with Dubrovnik literature imposing itself as a model, first in Dalmatia and later sporadically in the North.

3The concept of the ‘early modern’ in in Croatian literary history covers the period from the last quarter of the 15th century to the 1830s. In modern national philology, the entire history of Croatian literature is usually roughly divided into three periods : the Middle Ages (11th–15th century), the early modern period (15th century–1830s) and the modern period (from the 1830s onwards). Early modern literature is usually further divided into three (stylistic) sub-periods : 1) the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries), 2) the 17th century with the dominant Baroque poetics ; 3) the 18th century. The latter is characterized by stylistic pluralism (combining influences from the enlightenment, late Baroque, classicism, and pre-romanticism) and lasts into the first three decades of the 19th century, until the Illyrian Movement marked (as is traditionally understood) the beginning of the newer/modern Croatian literature. This briefly sketched periodization originated in the golden age of the immanent approach to literary history, in the mid-20th century, and has persisted to this day.

4To understand the development of early modern Croatian literature, it is important to point out some socio-cultural features of the Croatian lands of that time. Due to the lack of higher education institutions and the late establishment of printing houses (to a greater extent only in the last quarter of the 18th century), the domestic cultural/literary life was intensively linked to more developed neighboring regions in Italy and Central Europe. With the exception of communal schools in coastal towns during the Renaissance, the main domain of literacy were church institutions, especially in central and northern Croatia. The prevailing ecclesiastical provenance of written sources and poorly developed political life can explain the dominant conservatism of Croatian early modern culture. The sway of a “foreign power” over the Croatian lands, their peripheral position in the empires, and the metaphors of “long borders” and Antemurale Christianitatis were typically limiting factors for the development of early modern Croatian culture/literature, which are sporadically confirmed in contemporary literary sources (for example in anti-Turkish oratories and epistles in the 16th century).

5Croatian early modern literature is a “small literature” ; in some cases only a few texts represent a given genre or historical literary style, which facilitates their entry into the academic canon (university curricula and reviews of national literature). This is largely true of the early modern Croatian epic. Renaissance love poetry and 17th-century drama are rare examples of larger text production within one genre in Croatian premodern literature. On the other hand, Croatian literature of that period is characterized by a chronic lack of prose narrative fiction ; the only real exception is the pastoral novel Planine (The Mountains, written 1536, published 1569) by Dalmatian writer Petar Zoranić. This fact further reinforces the relevance of the narration in verse (epic). All in all, early modern Croatian literature can serve as a suitable model for comparative studies because it contains almost everything that great European literatures have, but to a lesser extent.

6The three concepts in the title of this article – ‘history’, ‘politics’ and ‘war’ – are semantically interrelated. ‘History’ means ‘cultural memory’, events from the past that still have some semantic value for the community ; ‘politics’ covers contemporary topics relevant to the community, i.e. ‘politics’ is a candidate for future ‘history’, and ‘war’ is a historical and political topic par excellence. In the Croatian early modern literature, these concepts are found across different genres, but their basic domain is still epic. This article will analyze the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Croatian epic texts on historical and political topics, while in the conclusion it will refer to some features of eighteenth-century epics.

II. Renaissance epic

-

1 Fališevac, Dunja, Kaliopin vrt : studije o hrvatskoj epici, Split, Književn...

7Croatian medieval literature offers no verse narrative comparable to contemporary epic works from more developed European literatures, such as Chansons de geste, La Chanson de Roland, Arthurian cycle/Chivalric romance etc. The probable reason for the absence of such epic texts is the non-existence of a highly developed feudal society with forms of court culture in Croatian lands.1 The Croatian medieval narrative in verse, already scarce in itself, deals only with religious themes. The oldest text is Pisan svetago Jurja (The Poem of St. George) from the end of the 14th century, while other versified legends of medieval provenance are known from later manuscripts (legends of St. Jerome, John Chrysostom, St. Catherine). With the genre-designation “secular novels” (“svjetovni romani”), Croatian literary historiography denotes prose narrative texts that deal with topics potentially suitable for epic verse treatment (the Trojan War, the life of Alexander the Great). In general, ‘history’, ‘politics’ and ‘war’ were not often thematized in Croatian medieval literature.

The beginnings of Croatian early modern epic literature : Marko Marulić’s Judita

8Marko Marulić (1450–1524), the author of the Renaissance biblical epic poem Judith, completed in manuscript in 1501 but not printed until 1521, is regarded as the founder of Croatian early modern epic. Marulić was aware of his founding role : he confirmed this in the preface to the epic poem, but also in a letter to his friend Jerolim Cipiko only a few months after the poem was finished. In the preface Marulić claims to follow the poetics of classical Virgilian epic, in the letter to Cipiko he compares his position in literature in Croatian language with that of Dante in Italian literature. The story of a pious and brave widow of about 300 biblical verses is retold through six cantos with a total of 2,126 dodecasyllables and a demanding rhyme scheme : the rhyme extends over four consecutive verses, appearing first at the ends of the lines and then at the hemistichs, as can be seen in the first eight lines of the epic :

9Dike ter hvaljen’ja presvetoj Juditi,

Smina nje stvore(n)’ja hoću govoriti ;

Zato ću moliti, Bože, tvoju svitlost,

Ne htij mi kratiti u tom punu milost.

-

2 Marulić, Marko, Judita, in : Hrvatski stihovi i proza, Lučin, B. (ed.), Zag...

10Ti s’ on ki dâ kripost svakomu dilu nje

I nje kipu lipost s počten’jem čistinje ;

Ti poni sad mene tako jur napravi,

Jazik da pomene ča misal pripravi.2

11The glory and the fame of Judith the blessed,

her hold deeds the same, to sing I’m possessed.

So, Lord, I’ve addressed my appeal for your light,

let it not be suppressed, grant your grace so bright.

-

3 Marulić, Marko, Judith, Translated by Graham McMaster, Most / The Bridge, 1...

12You imparted your might to her every feat,

made her fair to the sight, with chastity meet ;

Now this way I entreat you to lend me your aid

so the tongue can repeat what the mind has portrayed.3

13The epic version does not differ in basic content from the biblical source text : Marulić omitted data from the introductory part that are not relevant to the siege of Bethulia, while the additions and extensions of the biblical contents such as epic similes, catalogs, ekphrases and the like mostly derive from the poetics of the genre.

14The epic poem Judith was published three times during Marulić’s lifetime (1521, 1522, 1523) and two more times in the early modern period (1586, 1627), always in Venice. The influence of Marulićs work can be seen in the first historical Croatian epic Vazetje Sigeta grada (The Conquest of the Fortress of Szigetvár, 1584) by Barne Karnarutić, but not in the later epic texts, probably due to the loss of prestige of the Dalmatian Chakavian literary language during the 17th century.

15Since the 19th century Marulić has been designated as “the father of Croatian literature”, and by the decision of the Croatian Parliament from 1996, the April 22nd, the date on which Marulić completed his epic poem, is marked as the Day of the Croatian Book. The mission of “Marulianum, Centre for Studies on Marko Marulić and his Humanist Circle” in Split is to study and popularize Marulić’s work. The result of these efforts is that Marulić’s Judith is the most translated text of Croatian early modern literature (into English, French, Italian, Hungarian and Lithuanian).

16But why would an epic treatment of the Old Testament story of Judith be important to this topic ? The only way to find political meaning in Marulić’s text is its allegorical interpretation according to which the Jewish town of Bethulia under the siege of the Assyrian army represents the Christian town of Split under the attack of Ottomans. The question of the justification of the allegorical reading of Judith is still open in Croatian literary historiography. The arguments for an affirmative answer can be summarized as follows :

-

The time of the creation of the epic poem coincided with the Second Ottoman–Venetian War (1499–1503), during which the Ottomans attacked the hinterland of Split. The political situation at the time of the first publishing of Judith was similar.

-

Describing the Assyrian army, Marulić used some Turkish words (such as vezir, paša or subaša).

-

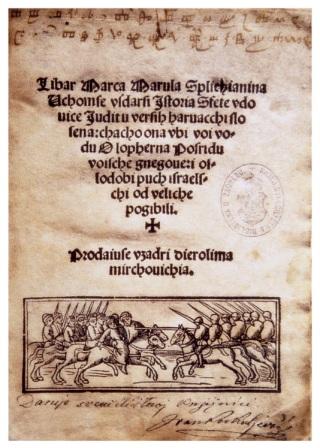

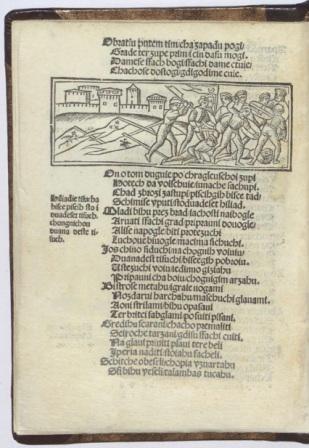

The woodcut illustrations in the second edition (1522) depict scenes from contemporary wars. The illustration on the title page shows the battle in which the soldiers of one side wear turbans and one illustration inside the book shows a (so-called) “Turkish flag”, i.e. the flag with the image of a dragon, which is a metaphor of the Ottoman Empire in early modern Christian literature and graphic art.

Marko Marulić, Libar Marca Marula Splichianina uchom se vsdarsi Istoria sfete vdouice Judit u versih haruacchi slosena, 2nd edition, 1552 (title page)

https://digitalna.nsk.hr/pb/ ?object =view&id =10063&tify =

Marko Marulić, Libar Marca Marula Splichianina uchom se vsdarsi Istoria sfete vdouice Judit u versih haruacchi slosena, 2nd edition, 1552 (p. 18)

17The counter-arguments are more persuasive :

-

In the text of the epic poem there is no reference to the contemporary political situation and no indication of allegorical interpretation ; in the preface, Marulić points out that he wrote Judith during Lent and emphasizes the Christian-moral meaning of the text.

-

The description of the Assyrian army contains many non-Turkish/-Oriental motifs :

-

Horsemen play the lute and drink in public, their flag is white-red, which are Hungarian-Croatian and not Turkish or Venetian colors, feudal dignitaries are called “barons”, just as in the French knightly epic.4

-

The woodcut illustrations in the second edition are not original, they come from a Venetian book published in 1516.5

-

6 Posset, Franz; Lučin, Bratislav (with the assistance of Branko Jozić), “Mar...

-

7 Pšihistal, Ružica, “Treba li Marulićeva Judita alegorijsko tumačenje ?”, Co...

-

8 Lokos, Istvan, “Još jednom o alegorijskom tumačenju Judite”, Colloquia Maru...

18As a citizen of the Republic of Venice, Marko Marulić did not have to write allegorically about the Ottomans. Moreover, he wrote several texts in Croatian and Latin featuring explicitly anti-Turkish statements.6 Therefore, it is more justified to place Judith in the context of other Marulić’s Christian-moral works of similar subject matter, as convincingly shown by Ružica Pšihistal in her synthetic study on the aporias about the interpretation of Marulić’s epic poem.7 However, in the last relevant article on this subject, the Hungarian Slavist István Lőkös advocates an allegorical interpretation, this time with comparative arguments : in the Hungarian literary genre of históriás ének (historical poems) from the 16th century, as well as in some contemporary texts in Polish and Czech literature about the biblical Judith, both a Christian-moralistic and an allegorical-political interpretation were implied.8 The comparison is admittedly only typological : all the listed works in Lőkös’ article are later than Marulić’s.

Introducing the poetic treatment of contemporary events : Barne Karnarutić’s Vazetje Sigeta grada

19The first undoubtedly relevant text for the topic of this article is the epic poem of the Dalmatian writer Barne Karnarutić Vazetje Sigeta grada (The Conquest of the Fortress of Szigetvár). The epic deals with the Ottoman siege of Szigetvár in 1566, it was probably written between 1568 and 1572 and first published in Venice in 1584, after the author’s death. Barne Karnarutić (1515 ?–1573) served in his youth as a captain of the Croatian cavalry in the Venetian army (Croati a cavallo), so he participated in the Third Ottoman–Venetian War (1537–1540).

20The Conquest of the Fortress of Szigetvár consists of four cantos of similar length with a total of 1,056 verses in double-rhymed dodecasyllabic couplets. In a short dedication to Juraj IV Zrinski – the son of Nikola Šubić Zrinski, the hero of the defense of Sizgetvár – Karnarutić places himself in the literary tradition of “old poets” who reveal in their verses “the courage of noble people”. The first canto, which is fully presented by the voice of the narrator, describes the gathering of the Ottoman army near Sarajevo (which is historically incorrect !). In the second canto, the Turks cross the Drava River over a bridge built with great difficulty, while the soldiers of Zrinski suddenly attack the vanguard of the sultan’s army at night and capture a huge booty. In the next canto, almost half of which consists of the characters’ direct speech (mostly Sultan Suleiman), begins a long siege of Szigetvár, initially unsuccessful, which provokes the anger of the Sultan. The last and fourth canto, shows the final fall of Szigetvár : Sultan Suleiman dies before the Turkish conquest of the fortress, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha conceals his death to the soldiers and incites them to a fiercer attack ; Zrinski gives his last speech to his soldiers and died in the assault, and Sokollu sends his severed head to the Habsburg emperor.

21The formal symmetry of the composition of the epic is not mirrored in the contents : some motifs are disproportionately long (for example, the description of Sultan Suleiman and his horse in the first canto covers almost a hundred verses), some are surprisingly short (Zrinski’s death is described in only two verses). Such structural disproportions, which do not exist in Marulić’s Judith, have led some literary historians to conclude that Karnarutić’s epic is an example of a mannerist (not Renaissance) style. On the other hand, numerous motivic and stylistic similarities of the two oldest longer epic texts in the Croatian language were noticed.

22The most important, but also the only hitherto proven source of content for Karnarutić’s epic is Historia Sigethi, a Latin prose description of the siege of Szigetvár, which was published in 1568 in Vienna by the Slovenian author Samuel Budina. The Latin text was soon translated into German and Italian, but it is assumed that the original was actually written in Croatian. One Croatian manuscript version in Glagolitic was found at the beginning of the 20th century ; the presumed author of the text is Ferenc Črnko, who took part in the defense of Szigetvár as chamberlain and secretary of Nikola Šubić Zrinski and fell into Turkish captivity, from which he was redeemed by Nikola’s son Juraj Zrinski. Črnko’s text is based on insider information from the besieged fortress and spy information about the Turkish camp. Therefore, Karnarutić’s additions mainly concern events in the Turkish army, described in the first canto. The explication of the political meaning of Karnarutić’s Conquest must therefore start from the comparison of the two texts. Črnko’s description of the Siege is dominated by the referential function, featuring very few value or ideologically colored statements : the Turks for instance are mostly designated with value-neutral attributes. The rare ideological statements are found exclusively in Zrinski’s speeches. In the oath before the siege begins, he pledges himself first to God, then to the emperor, and finally to his homeland. In the speech before the final battle, Zrinski designates the Turkish siege of Sizgetvár as God’s punishment for the “sins of other countries”.

23All these components, but to some extent significantly changed, also appear in Karnarutić’s text. The evaluation of the Turks through the voices of the narrator and Christian characters is more intensive than in Črnko’s account : the Turks are represented as religious enemies, the Battle of Sizgetvár is defined as primarily an episode of the Christian-Islamic War, and Zrinski swears only to God. On the other hand, and in accordance with the classical epic tradition, the leading characters of the opposing side – Sultan Suleiman and Sokollu Mehmed Pasha – are evaluated extremely positively within the narrator’s voice. Zrinski in his last speech also defines the Turkish attack on Sizgetvár as God’s punishment, but the sin is more specific here – he alludes to apostates from the faith in his own country (Calvinists), in an explicit comparison with the French Huguenots. The differences in the two texts can perhaps be explained by where their authors’ loyalties laid : with the Venetian one for Karnarutić, and with the Habsburg for Črnko (and Zrinski).

-

9 Lőkös, István, “Recepcija Karnarutića u mađarskoj književnosti”, Croatica ...

24As the first Croatian epic about a contemporary political event, Karnarutić’s Conquest has a guaranteed place in the academic literary canon. On the other hand, Croatian literary historians constantly point out the aesthetic shortcomings of the text, especially in comparison with Marulić’s Judith. More relevant for the subject matter of this essay is the fact that the Conquest was published twice in the 17th century : first in Venice in 1639, and then in an unknown place, probably in 1661, in the orthography used in northern Croatia. Meanwhile, Nikola VII Zrinski wrote and in 1651 published an epic in Hungarian about the same event (Szigeti veszedelem). Hungarian literary historians have shown that their Baroque poet read Karnarutić’s text and used it as one of the sources for his epic.9 The Hungarian epic poem about the Siege of Szigetvár was soon translated into Croatian by Nikola’s brother Petar Zrinski, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section. In any case, Karnarutić’s text is important for the history of Croatian literary culture of the 17th century as well.

Chronicling the ongoing Turkish wars : Antun Bratosaljić Sasin’s Razboji od Turaka

25The first epic text on political themes in Dubrovnik literature was written only at the end of the 16th century. The playwright and poet Antun Bratosaljić Sasin (c. 1518 – 1595 ?) wrote, probably in the last three years of his life, the unfinished epic Razboji od Turaka (Battles of the Turks ; it is the newly coined title according to the titles of individual cantos of the epic). The core of the epic was a poem of 82 double-rhymed dodecasyllabic verses dedicated to the Battle of Sisak in 1593. The author, however, continued to write about the events of the Long Turkish War (1593–1606), until the fall of the fortress of Győr (Ger. Raab) in November 1594, i.e. until the death of Sultan Murad III in January 1595. Since Sasin does not describe the war events of 1595, it is assumed that he died that year.

26After the poem about the Battle of Sisak, Sasin changed his metrics, and went on writing in enclosed-rhyme octosyllabic quatrains (abba). The final version of the epic comprises nine unequal cantos with a total of 1,820 verses. The theme of the epic is war, there is no unique story or protagonist, the focus shifts (in chronological order) from battlefield to battlefield. There is no traditional epic narrator either, but instead a Fairy (Vila) acting as a female messenger of events from the battlefields. She transmits her reports to a character named Sas – the poet’s alter ego, who turns Fairy’s oral news into verses. The Fairy is a well-informed narrator : she accurately dates each event, describes the movement of armies, their size and losses in battles. At the same time, Fairy is also a very naive narrator : she unequivocally supports the Christian side in the war and describes the battles in which the Christians won, with the exception of the fall of Győr ; Fairy avoids political comments as well as explicitly negative evaluation of characters of the Turks.

27The Battles of the Turks was not published during the early modern period, nor is its influence on later Dubrovnik epic texts noticeable. Sasin’s sources have not been revealed, but the epic’s primary intent seems to have been to inform fellow citizens about the events of the Long Turkish War. The anti-Turkish tendency in the epic certainly could not have contributed to its public dissemination, given the delicate political relations of the Republic of Dubrovnik towards the Ottoman Empire. And as for the poetics of the epic, it is interesting that epic texts like Battles of the Turks – with a chronological composition, a fragmented storyline and a primary reporting function – will appear in greater numbers only in the 18th century.

Longer and shorter epics on contemporary events

28In the 16th century only two longer epic poems were written (and published) in the Croatian language on contemporary political events. In addition, six short epic texts from the same period on similar topics have been preserved. Here they are, in the chronological order of the events they relate.

29The Battle of Mohács in 1526 and the death of King Louis II of Hungary (Jagellon) is an important event in the Croatian national historical narrative, which marks the beginning of a long era of Habsburg rule in the Croatian lands (1527–1918). This event is the focus of Razboj i tužba kralja ugarskoga (The Battle and Lamentation of the King of Hungary) of 336 double-rhymed dodecasyllabic verses – preserved in a manuscript with texts of Dalmatian Chakavian literature, including two poems by Marko Marulić. The narrator of the poem, whose author is probably an unknown poet from Split or Hvar, is the unfortunate young king. He depicts the battle as an episode in a religious war and sends two political messages : the need to unite the currently divided Christian forces in the war against the religious enemy (the Turks), and the praise of Pál Tomori (archbishop of Kalocsa and the leader of the Hungarian army, who died in the battle) as a war hero rather than the one responsible for the defeat, contrary to what can be read in many contemporary sources.

30The Great Siege of Malta in 1565 is the subject of another anonymous poem in Dalmatian Chakavian literature (Pisam od Malte/The Poem on Malta). The exact date of the text is unknown, but it was published three times during the early modern period (1655, 1699 and 1724), always in Venice, and accompanied by another poem with a shared title : Skazovanje od čudnovate rati, ča je bila pod Maltom a za njom nasliduje rat od Klisa (The Story of the Strange Battle, which Was near Malta, Followed by the Battle of Klis). The poem consists of 526 double rhymed octosyllables arranged in octaves ; its low poetic style is based on the vernacular spoken idiom, and its thematic and ideological level is characterized by the reporting function and militant Christian propaganda. Due to all this, the poem did not meet with much interest in Croatian literary historiography, so many questions remain open to this day (who is the author of the poem ? What sources did they use ? Why was it first published almost a hundred years after the event, supposing the 1655 edition is the oldest ?)

31The only short epic text in this review, which is composed of several cantos and can be called a small epic, is the Kajkavian Pjesma o Sigetu (Poem of Szigetvár, an editorial title), preserved in a manuscript of Kajkavian and Slovenian texts from the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The only known version of the text is incomplete, missing the beginning and middle of the last, fourth canto ; the preserved parts include 377 irregular and unrhymed verses. The basic plot does not differ from the two older texts on the same topic (discussed above), but the differences in the individual motifs are significant. First, Nikola Zrinski twice unsuccessfully calls for help from the king, who follows the advice of his counsellors not to send help in spite of his own desire to do so. Second, the narrator points out that Nikola Zrinski has two enemies in his own camp : one at the Viennese court, the other in the nearby province of Međimurje. And third, the author changes the order in which the two main characters die : Nikola Zrinski dies first, so Sultan Suleiman can praise the defender of Szigetvár at the end of the epic. The stated content details speak in favor of the political-polemical potential of this text.

32The last three short epic texts in this catalog all deal with events from the Long Turkish War (1593–1606), their content therefore coinciding partly with the epic of Antun Bratosaljić Sasin.

33The shortest is Od Siska grada verši od boja (Verses about the Battle of Sisak), consisting of only 66 partly irregular verses, partly double-rhymed dodecasyllables. It has been preserved in a manuscript, and was probably created immediately after the described events, the Habsburg-Ottoman Battle of Sisak in 1593. The poem is composed in the style of a traditional epic, as a conversation between a girl and a participant in the battle, and celebrates the victory of the Christian army.

34Govorenje od vojske od Janoka (Telling about the War at Janok) is also preserved in one manuscript, but from the Štokavian-speaking area ; it comprises 261 irregular partially rhymed verses and is divided in two parts. The first part describes the Ottoman conquest of the fortress of Győr in 1594, as well as the last canto of Sasin’s Battles ; the second part depicts the Habsburg reconquest of the fortress in 1598. In addition to its reporting function (for example, the Ottoman conquest is described as a consequence of betrayal, which corresponds to historical sources), the poem is also marked by expressions of radical militant Christianity.

35The last short epic poem in this corpus is Boj ili vazetje od Klisa (Battle or the Conquest of Klis), consisting of 178 double-rhymed dodecasyllables, published together with the epic poem about the Great Siege of Malta in 1565 (Venice 1655, 1699, 1724). The theme of the epic poem is a lesser event of the Long Turkish War, the short-lived Christian conquest of the fortress of Klis in 1596 by a group of Split nobles. The fortress of Klis near Split, of great strategic importance in the early modern period, was conquered by the Ottomans in 1537. The Christian fighters, while they were subjects of the Venetian Republic, expected military assistance from the Habsburg army, which was not enough to keep the fortress under their control. The poem is structured as an exchange of letters between the leader of the Christian fighters, Ivo (the historical Ivan Alberti), and the Habsburg emperor. The poem points out the insufficient Habsburg help : only less than a thousand infantry arrived (without cavalry), so the Ottomans easily recaptured the fortress. Accordingly, the poem is primarily a political controversy within the Christian camp.

III. The seventeenth-century Baroque epic

36In the seventeenth century Croatian literature (including the first two decades of the next century), there are only six longer narrative texts in verse on secular themes. Four of them belong to the type of epic established in European literature by Torquato Tasso (Dž. Gundulić, P. Zrinski, J. Palmotić Dionorić, P. Kanavelić), one text is a chronicle in verses like Sasin’s Battles (P. Bogašinović), and one is a genre-indeterminate epic (J. Baraković). One epic was translated from Hungarian (P. Zrinski), and the others are original works. Here they are in chronological order.

A Slavic epic : Juraj Baraković’s Vila Slovinka

37The epic poem Vila Slovinka (Fairy of the Slavs, Venice 1614, 1626, 1682) by the Zadar poet Juraj Baraković (1548–1628) consists of nine unequal cantos for a total of about 9,300 verses in various meters and stanzas. The text is artificial not only at the formal but also at the content level. The protagonist, the writer’s alter ego, who is simply called the Poet (Pisnik), recounts the events he experienced in four trips in the surroundings of the Dalmatian city of Šibenik. The history of the Poet’s family, of his hometown of Zadar as well as his existential doubts are revealed in conversations with the characters he meets on his trips. The title of the epic is actually the name of the protagonist’s main interlocutor : the Fairy is the main narrator in the first seven cantos. Different thematic worlds appear in the text : the historical one is prominent, but there are also mythological and eschatological ones.

38The political meanings of the epic poem are substantial and complex, and can be briefly defined as a mixture of Slavophile, Hungarophile and anti-Turkish ideas with an ambivalent attitude towards the Venetian Republic. In the second canto, the Fairy describes in Virgilian style the preparation of Zadar (construction of ramparts) for the upcoming Ottoman siege during the War of Cyprus (1570–1573), which is the main theme of the third canto. The Fairy depicts only the war events in the city and its surroundings without a broader political context, and does not even explain the reasons for the end of the war, i.e. for the end of the siege. The Venetophile and anti-Turkish tendencies of this description are obvious. Moreover, anti-Turkish ideas are one of the semantical constants of the epic poem : already in the first canto, the Poet claims that he cannot come to his estates in the Zadar area due to Turkish occupation ; in the dedication and in the final cantos, there are verses of praise for the local fighters against the Turks, but the most important motifs of this segment of the political meanings of the epic can be found in the twelfth canto. After some personal crises, the Poet arrives by boat on an island where the cave is located, which is actually purgatory and hell. This space will be shown to the Poet by the Shadow of Envoy, with whom the Poet walked back to Šibenik in the eighth canto. The Envoy was in the service of the Ottoman authorities in the neighboring province of Herzegovina, he told the Poet about his meeting with some Zadar noble families and conveyed the news of the death of Poet’s brother and nephew. He went to hell because of lies about some Zadar nobles, told in an effort to stop serving the Turks and move to Zadar. The only historical figure in Baraković’s hell is the Serbian despot Đurađ Branković : his mortal sin is the betrayal of John Hunyadi and other Hungarian fighters against the Turks, i.e. non-participation in the Second Battle of Kosovo (1448). Thus, the only two characters of the (quasi)historical world who got to hell are connected by the sin of betraying the Christian side and serving the Turks.

39Hungarophilia dominates the first canto of Baraković’s text, in which the Fairy tells of the Poet’s ancestors. His great-grandfather Bartul served the Hungarian king Bela, successfully fought against the Tatars, for which he received a title and three villages in the vicinity of Zadar. The Fairy then continues to narrate the history of Zadar : in the battles between the Venetians and the Hungarian king for Zadar, the people of Zadar constantly remained loyal to the king. The critical point in this story is the sale of Dalmatia to Venice by Ladislaus of Naples in 1409, which the Fairy describes in the following eight verses :

jer kad se izpuni vrimena niki broj,

svitli kralj napuni razpusti šereg svoj,

već ne hti biti boj ; tako se dogodi

da pusti nepokoj u mirni slobodi.

Svitli kralj pogodi rad vičnje odluke,

bnetačkoj gospodi da Zadar u ruke

10 Baraković, Juraj, Vila Slovinka, in : Djela Jurja Barakovića, Zagreb, Jugo...

prez rati, prez buke, za mito mnju niko, Prijatje od Zadra.

prez truda, prez muke, Vičnji zna koliko.10

because when a certain time passed,

the bright king disbanded his troops,

and did not want to continue fighting ; so it happened

that peaceful freedom came after the unrest.

The bright king, because of the decision of the Most High,

gave Zadar into the hands of the Venetian nobility,

without war, without noise, for a gift, I mean, The takeover of Zadar.

without effort, without torment, the Most High knows the price.

-

11 On the image of Venice in Baraković’s epic, see Dukić, Davor, “Das Geschri...

40Thus, the Fairy presents the act of political calculation as a somewhat incomprehensible decision of God. The political sphere is not secularized in Baraković’s epic poem : power is given by God and loyalty is a natural state. Accordingly, the typically mediaeval social order of the city of Zadar, presented in the sixth canto of the epic, is recognized as God-given. But Hungarophile and Venetophile feelings are mutually exclusive when describing the Hungarian-Venetian struggle for Dalmatia in the late Middle Ages : the attitude towards Venice in Baraković’s epic is therefore ambivalent. However, the text lacks direct criticism of Venice, as the Fairy simply conceals the controversial siege of Zadar in 1202 during the Fourth Crusade.11

-

12 For an interpretation of Baraković’s epic from a psychoanalytic perspectiv...

41The emphasizing of Slavophilism/Croatophilism/patriotism in Baraković’s epic poem is one of the commonplaces in Croatian literary historiography. The title of the text itself points to this value idea : it not only denotes one of the characters/narrators, but also determines the cultural/linguistic affiliation of the epic. In this sense, Baraković’s patriotism is primarily a cultural one : the other side is written culture in Latin/Italian, which, in the writer’s opinion, dominates in his homeland as well. On the other hand, the geo-spatial scope of this patriotism does not exceed the borders of Baraković’s own homeland, in fact the two communities in which Baraković lived : Zadar and Šibenik. It has long been known that for some reasons, which are still not entirely clear, Baraković was expelled from the Zadar community at the beginning of the 17th century, so he spent most of the rest of his life in Šibenik. For Baraković, this was a traumatic event about which the author leaves traces in the epic poem, and his medieval communal patriotism hesitates sporadically in the text between the two Dalmatian communities.12

Dživo Gundulić’ Osman

42The epic poem Osman by the most famous Dubrovnik seventeenth century poet Dživo (Ivan) Gundulić (1589–1638) is a canonical text of older Croatian literature, and its most popular epic. This text influenced a large number of the later early modern Croatian epic poems, not only in Dubrovnik literature, and is an integral part of compulsory high school reading (albeit only in selected fragments). This literary-historical status of the text is even more impressive when two additional facts are taken into account : the epic remained unfinished, and it circulated throughout the early modern period exclusively in manuscripts. The aesthetic quality of the text, especially regarding style, but also the compatibility of its ideological messages with different national ideologies, overcame its formal deficiency and limited dissemination. The literary-historical literature on Osman is extremely abundant, and is marked by a polemical discussion of a number of open questions : What is the main theme (plot) of the epic, i.e. who is the main character : the Polish Prince Władysław Vasa or the Ottoman Sultan Osman II ? Was the epic written as a single text or was it created by merging the two texts : one about the Battle of Khotyn (1621) and the other about the overthrow of Sultan Osman II (1622) ? Were the two missing cantos of the epic lost or were they never written ? Does the only canto of the epic whose plot is set in hell come before or after the missing cantos, i.e. should it be marked with the ordinal number 13 or 15 ? The following short review is based on today’s prevailing literary-historical insight into the text.

-

13 As per the critical edition in the series “Stari pisci hrvatski”/“Old Croa...

43Gundulić had intended to translate Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered, but after the overthrow of Sultan Osman II he gave up that intention and decided to write an epic about this contemporary political event. As far as we know today, Gundulić failed to complete this literary project before his death. The eighteen completed cantos contain 10,428 octosyllables13 arranged in alternate-rhyme quatrains (abab), a format that would become dominant in later Dubrovnik epics. The overthrow of Sultan Osman II is the main theme of the epic and Sultan Osman is both the title and the main character, but much of the narration is dedicated to the Battle of Khotyn and Polish Prince Władysław.

44The Battle of Khotyn is represented in the epic only retrospectively, on three occasions, and in three different ways : an account of participants in the battle (cantos IV and V), an inserted poem (canto X), and an artistic depiction on the tapestries of the Court in Warsaw (canto XI).

45On the other hand, the Istanbul Coup is related as a continuous epic narrative in the final cantos (XVI–XX). The first two cantos are written in the present time of the epic plot (meaning after the Battle of Khotyn), show Sultan Osman with his closest advisers (the Grand Vizier, the Qadi and the Chief Eunuch of the Sultan’s harem) making two decisions that guide the storyline of the epic before the lacuna of the two missing cantos : (1) to conclude a truce with the Kingdom of Poland the Ottoman delegation led by diplomat Ali-pasha travels to Warsaw (cantos III–VI, IX–XII), while an expedition led by the Chief Eunuch Kazlar-aga travels to Greece and Serbia to fulfill another decision (2) : to find girls of noble birth for the Sultan’s harem (cantos VII–VIII). In the first canto the young Sultan also makes the most important, fateful decision : to undertake an expedition to the East of the Empire to replace his current janissary troops, all under the pretext of going on a pilgrimage to Mecca. That expedition will not happen because the secret plan has been revealed and the Sultan will be killed in a janissary rebellion.

-

14 On the history of Poland in Gundulić’s epic, cf. Bojović, Zlata, Osman Dži...

-

15 Kravar, Zoran, Das Barock in der kroatischen Literatur, 123.

-

16 Ćosić, Stjepan ; Vekarić, Nenad, “Raskol dubrovačkog patricijata”, Anali D...

46The most important deviation in the epic from confirmed historical events is related to the political values promoted by the text. In the epic, the Ottoman delegation travels to Warsaw to negotiate peace before the Coup in Istanbul, while in reality the opposite was true : Poles traveled to Turkey after the overthrow of the Sultan. Thus, Gundulić opened the space for Polonophile statements : for praises to Prince Władysław, to the Polish army and to the Polish form of government.14 In the older literary historiography, the Slavophilia was emphasized as one of the main semantic/ideological features of Gundulić’s epic, but positive feelings are not tied to the whole Slavic space. Apart from the dominant Polonophilia, the positive values are linked to the South Slavic area, especially to the Serbian Despotate and Dubrovnik (canto VIII), but not to Czechs and Russians (cantos X–XI).15 A similar ambivalence characterizes the representation of the Turkish side in the epic. The title character is, especially in the first canto, portrayed as an embodiment of the sin of pride and youthful recklessness, but in the depiction of the Istanbul coup the narrator unequivocally stands on the side of legally established government. The Grand Vizier Dilaver, the personification of political loyalty and the main helper of the endangered young Sultan (which is admittedly in contrast to the historical truth), is the second most positive character in the epic, right behind Prince Władysław ; on the other hand, the most negative characters are the rebel leader Daut and the mother of the former Sultan Mustapha (uncle of Sultan Osman II), Daut’s mother-in-law, who is portrayed in the epic as the originator of the plan of rebellion (canto XVII). The dominant value perspective of the epic can be defined as Dubrovnik-aristocratic, and its initial values are at the same time the attributes of a possible Dubrovnik auto-image : ‘Christianity’, ‘Slavism’, ‘republicanism’, ‘legitimate and traditional government’, ‘peaceful politics’. Gundulić’s narrator considers political rebellion a dangerous event for any community (canto VII), and that the fear of rebellion in his own homeland could have oppressed the real author is shown by contemporary studies of political disputes in the Dubrovnik nobility of the 17th century.16

-

17 Cf, Dunja Fališevac, “Kompozicija i epski svijet Osmana (iz vizure naratol...

47In contrast to Juraj Baraković, Gundulić’presents politics as an emancipated human activity in his epic. This is particularly evident in Ali-pasha’s “modern” political speech at the Warsaw Court (canto XI).17 Moreover, Lucifer’s speech in the council of hell (canto XIII/XV) has similar characteristics. It must be noted that in literary historiography Gundulić’s hell is characterized as dysfunctional in the storyline, as a mere ornament taken from the Virgilian/Tassian literary tradition.

-

18 Cf. Kravar, Zoran, Das Barock in der kroatischen Literatur, 121–135

-

19 The thematization of the recent political event can also be considered as ...

48In Gundulić’s epic, the historical thematic world is extremely dominant. With this insight, Zoran Kravar explained the problem of the missing cantos : Gundulić, following Tassian poetics only in part, formed too few romantic characters, exclusively female (women warriors Sokolica, Krunoslava and Begum, and the idyllic beauty Sunčanica), which led to close connections of historical male and romantic female characters (Osman–Sokolica ; Dilaver–Begum, probably Osman–Sunčanica in the missing cantos). Gundulić failed to resolve these connections, so the epic remained unfinished.18 In this sense, the lack of two cantos of the epic can be considered as a poetic shortcoming as well, which did no harm at all to the canonical status of the epic.19

Back to Szigetvár : Petar Zrinski’s Obsida sigecka

-

20 On literary adaptations of this topic, cf. Dukić, Davor, “The Zrinski-Fran...

49The second extensive epic poem in Croatian literature about the 1566 Siege of Szigetvár was written by Petar Zrinski (1621–1671), the great-grandson of the legendary defender of the fortress Nikola Šubić Zrinski. It is actually a translation of the Hungarian epic of his slightly older brother Nikola Zrinski (Zrínyi Miklós, 1620–1664), the Croatian ban and one of the initiators of the anti-Habsburg Conspiracy of Hungarian magnates (Wesselényi or Zrinski-Frankopan Conspiracy). After Nikola’s controversial death during a hunt in 1664, both the title of Croatian ban and the leadership of the Conspiracy were taken over by Petar Zrinski. Later, in 1671, after the disclosure of the Conspiracy and the trial of its leaders, Petar was executed together with his young brother-in-law and accomplice Fran Krsto Frankopan. This is usually considered as one of the most traumatic events in the Croatian national historical narrative, a kind of breakdown of the Croatian nobility.20

-

21 Cf. Novalić, Đuro, Mađarska i hrvatska “Zrinijada”, Zagreb, Filozofski fak...

-

22 Numerical data and insights into the semantic differences between the two ...

50In Croatian literary historiography, Petar Zrinski’s epic Obsida sigecka (The Siege of Szigetvár), published along with several shorter poetic compositions in a book entitled Adrijanskoga mora sirena (The Siren of the Adriatic Sea, Venice 1660) is usually not considered a mere translation of the Hungarian original Szigeti veszedelem, i.e. Adriai Tengernek Syrenaia (Vienna 1651). First, as mentioned above, Nikola Zrinski used the Croatian epic poem of Barne Karnarutić as one of the sources (his main Hungarian Latin sources were the historiographical works of Miklós Istvánffy and János Zsámboky). Furthermore, a rather bold thesis on the influence of South Slavic oral epic on the Baroque epic poem of Nikola Zrinski has been quite convincingly argued.21 Finally, and also the most important, Petar Zrinski made some indicative substantive changes in his translation. His epic consists of 15 cantos with 1,699 quatrains composed of double-rhymed (i.e. rimed both at the caesura and the end) dodecasyllables (ab/ab/ab/ab), i.e. with a total of 6,796 verses. The differences between the Croatian translation and the Hungarian original can be expressed numerically as follows : Petar Zrinski omitted 41 Hungarian quatrains, substantially changed 15, in 21 cases translated one Hungarian with two or more Croatian stanzas and added 137 quatrains of his own.22 The most important content/semantic changes concern the replacement of the original collective identity attribute ‘Hungarian’ with the attribute ‘Croatian’, a more negative representation of Sultan Suleiman and other Turkish characters, the adding of religious/Christian motifs and, above all, the insertion of general considerations, for example, on the instability of human happiness. One omission is also important for the semantic potential of the Croatian translation. Petar Zrinski did not translate nine stanzas at the beginning of canto XIV – the only current-political commentary in his brother’s epic poem, in which Nikola Zrinski praises his brother Petar, expresses feudal self-awareness, and implicitly criticizes the Habsburg government, a way of hinting at the Conspiracy. The decision on the content deviations from the original was made by Petar Zrinski during the translation : the first version of the translation covering approximately half of the epic is preserved in the manuscript, and is more faithful to the original in terms of both content and versification (verses are not double rhymed). Everything else relevant to our study of the ‘representation of history’ is common to both the Hungarian epic and the Croatian translation.

51The most general conclusion is that the historical layer is the most important component of Nikola Zrinski’s epic. He consulted relevant historiographical sources of his time (Istvánffy, Zsámboky) ; moreover, he justifies even the most striking deviation from the generally accepted historical assumption (that Sultan Suleiman died a natural death before the fall of Szigetvár e.g.) by referring to unnamed Croatian and Italian chronicles. In his epic, the Sultan is killed by the author’s great-grandfather (Petar Zrinski did not take that motif in his translation). However, Nikola Zrinski told the historical story in a conventional literary way, in the style of Tassian epic, and he did it in a poetically more successful way than Dživo Gundulić.

-

23 Cf. Bitskey, István, “Pogled na povijest i slika nacije u epu Nikole Zrins...

52While in Gundulić’s epic the forces of the Hell appear relatively late and without influence on the plot, in Nikola Zrinski’s epic the forces of the Heaven and Hell act at the beginning and determine and explain the fate of the community that should consider the text as their own epic poem. Already in the first canto God determines the fate of Szigetvár and its defenders : the Ottoman conquest is part of a divine plan to punish the sinful Hungarians. The righteous people will also be punished, but only on Earth. The punishment/temptation will last for three generations, so if the Hungarians do not morally reconcile by then (i.e., by the time the epic was written), God will punish them forever. God therefore sends Archangel Michael to take the fury out of Hell and incite Sultan Suleiman to war against the Hungarians. The stereotypical motifs of classical epic are nevertheless explained in Hungarian literary historiography in the context of the early modern narrative of Hungarian history according to which the Ottoman conquest of the country was God’s punishment after the golden age, i.e. after the late medieval prosperity of the Hungarian state.23 The forces of Heaven and Hell reappear in the last two cantos, and at the very end the Archangel Gabriel announces to Nikola Zrinski Sigetski his departure for Heaven. Other literary devices of classical/Tassian epic also appear in the text (however Nikola Zrinski refers to Homer and Virgil, and not to Tasso !) : duels of the heroes of the two warring parties, the miraculous motifs, a love episode and the anger of one of the heroes as digressions in the plot. All in all, the function of the epic poems of the Zrinski brothers was to celebrate their magnate family, to politically activate their contemporaries and like-minded people, and, ultimately, to confirm themselves as skilled poets.

-

24 This is the first published text of Dubrovnik literature with explicit ant...

53Petar Zrinski is considered a member of the Ozalj literary-linguistic circle (a seventeenth-century group of writers and linguists from central Croatia) from the area where the estates of the noble families Zrinski and Frankopan were located (the town of Ozalj belonged to the Zrinski family). The language of the Circle is hybrid : it is characterized by a Chakavian basis with Kajkavian and Shtokavian elements. Petar Zrinski’s epic was published only once in the early modern period, its second edition appeared only in 1957, as a critical edition. Nevertheless, The Siege of Szigetvár is considered an influential text : two literary works printed in the 17th century were created under its direct influence. First, the Dubrovnik writer Vladislav Menčetić (1617–1666) published in 1665 a poem entitled Trublja slovinska (The Slavic Trumpet), dedicated to Petar Zrinski and his epic.24 Then Pavao Ritter Vitezović (1652–1713), who is also considered a member of the Ozalj circle, printed on three occasions in the late 17th century the poem Odiljenje sigetsko (The Szigetvár Farewell, 1684, 1685, 1695). The poem is composed of a series of short lyrical texts (letters, conversations, epitaphs) which are actually reminiscences of the Siege of Szigetvár presented in the epic by Petar Zrinski ; without knowledge of Zrinski’s epic poem Vitezović’s text cannot be understood.

An unfinished epic : Jaketa Palmotić Dionorić’s Dubrovnik ponovljen

-

25 Holthusen, Johannes, “Einleitung”, in: Palmotić, Jaketa, Dubrovnik ponovlj...

54The epic Dubrovnik ponovljen (Dubrovnik Restored) by diplomat and writer Jaketa Palmotić Dionorić (1623–1680) holds a different status (compared to Petar Zrinski’s epic) in the contemporary/early modern reception in its own literary community. The text remained unfinished (albeit only in a technical sense, as the missing verses of the last canto could not change the plot) and unpublished until the late 19th century, without influence on later Dubrovnik early modern literature. It had only three complete editions in modern times (Dubrovnik 1878, Munich 1974, Dubrovnik 2014), which is not a particularly impressive number, but thanks to its unusual and interesting topic, the epic still has a prominent place in the academic canon and is relatively well studied.25

55In the context of this article, the importance of Palmotić Dionorić’s epic is comparable to the epic of Dživo Gundulić : both poets write about a contemporary event that will surely be recorded in history. The main theme of the epic Dubrovnik Restored are the political consequences of the Great Earthquake in Dubrovnik in 1667. The political context of the earthquake is the Cretan War (1645–1669), but the war itself is not thematized in the text, and only one war scene features in the epic. However, the threat of war, i.e. the military conquest of destroyed Dubrovnik, is present throughout the epic. Politics is the main theme of Dubrovnik Restored, and no other text in early modern Croatian epic literature would be more political in the literal sense.

56Palmotić Dionorić’s epic contains autobiographical features. The text recounts what the author directly experienced (the loss of his wife and children in the earthquake, a remarriage with a woman of similar fate, a diplomatic mission to Istanbul), what he heard from witnesses of current events (the earthquake, re-establishment of power in the destroyed city, negotiations with representatives of the Venetian and Ottoman Bosnian authorities) and what he invented in accordance with the classical/Tassian poetics of the epic (events in Heaven and Hell, i.e. the action of their forces, exciting adventurous episodes on the diplomatic travels of the protagonists).

57The epic consists of twenty cantos totaling 3,911 octosyllabic quatrains in alternate rhyme (abab), i.e. a total of 15,644 verses. The narration begins with a description of the organization of life in Dubrovnik a few days after the earthquake. In the second canto the forces of the Heaven are introduced : God – through the intercession of St. Blaise (Sveti Vlaho), the patron saint of Dubrovnik – forgives the citizens of Dubrovnik for the sin of pride that led to the earthquake and guarantees them the reconstruction of the city and a secure political future. These heavenly promises begin to be fulfilled in the third canto : Dubrovnik receives food aid from the pope and military aid from the king of Spain, but then the forces of Hell get involved in the story. They encourage the kaymakam Mustaj-pasha (who rules in Istanbul while the Grand Vizier is at war with the Venetians in Crete and the Sultan Mehmed IV is hunting as usual) to ask Dubrovnik for an increased annual tribute (300 extra sacks of treasure) for the property of citizens who died in the earthquake and have no heirs. Therefore, Mustaj-pasha imprisons Dubrovnik’s diplomatic representatives in Istanbul and orders the Bosnian Pasha to besiege Dubrovnik (canto IV). In the fifth canto, the further course of the plot is determined. As the Bosnian army approaches Dubrovnik, one part of the Dubrovnik nobles of the Grand Council proposes that the city be handed over to the Venetians, and the other part that a mercenary be hired to defend the city. The dilemma is resolved by the hermit Pavo who comes to the Council from the nearby island of Daksa. He conveys the message of Saint Blaise to the people of Dubrovnik to persevere in fidelity to God and that they should not be afraid of hellish forces or enemies ; they need to be brave, and the sultan will soon relent. Accordingly, the Grand Council decides to send three diplomatic delegations : to the Sultan, to the Bosnian Ali Pasha and to the Venetian general whose ship is in the port of Dubrovnik. The latter delegation manages to persuade the Venetian general not to occupy the city, but to stay in port to help Dubrovnik in the event of an attack by the Bosnian Pasha’s army. Only one Dubrovnik nobleman named Kuničić (historical Marko Gučetić, the poet’s cousin) goes to negotiate with the Bosnian Pasha ; his journey is described in canto VI and his negotiation with the Bosnian Pasha in canto VII. The Pasha temporarily gives up the attack on Dubrovnik, but keeps the Dubrovnik diplomatic representative in prison. The central part of the epic is the diplomatic mission of the two Dubrovnik nobles (Jakimir and Bunić – Nikolica Bunić, Dubrovnik poet and diplomat) to the Sultan, with the aim of paying only the usual annual tribute (cantos VIII–XVI). The main character of the epic, the author’s alter ego Jakimir, does not enter the scene until canto VIII, which describes his fate : the death of his wife and four children in the earthquake, while he was on his way from Istanbul to Dubrovnik ; his remarriage with Jelinda who also lost her husband and child in the earthquake. From the ninth to the eleventh canto, the journey of the Dubrovnik delegation through Serbia and Bulgaria to the Sultan is described. The next four cantos present the negotiations of two Dubrovnik diplomats with representatives of the Ottoman authorities, with two culminating points : Bunić’s speech on the earthquake (canto XIII) and the ceremony of handing over the annual tribute to the sultan (canto XV). With their diplomatic skills, the Dubrovnik delegates managed to appease the kaymakam, who was initially very averse to them, and finally they successfully fulfilled their task. But in the sixteenth canto, the forces of the Hell intervene again : the King of Hell releases the monster Greed, which encourages the Sultan to ask the Dubrovnik diplomatic representatives again for 300 sacks of treasure. Jakimir and Bunić cannot fulfill that request, so they end up in custody. In the seventeenth and eighteenth cantos, the action takes place again in the territory of the Republic of Dubrovnik : the defenders of Dubrovnik win the battle with a detachment of the Bosnian Pasha’s army, but Dubrovnik still fears the Bosnian army. While unfavorable news from Turkey is being read in the Grand Council, the hermit Pavo from the island of Daksa comes again and confronts the Dubrovnik nobles : he tells them that Saint Blaise is still supporting Dubrovnik and that he helped fight the army of the Bosnian Pasha (canto XVIII). In the penultimate canto, the celestial forces are reactivated : Saint Blaise returns to Hell the monsters who encouraged the Turks to greed, and brings out of Hell the Prophet Muhammad, who subsequently appears to the Sultan in a dream and forces him to give up the pressure on Dubrovnik and to remain its political protector. In the written part of the unfinished twentieth canto of the epic, the released former diplomatic representatives of Dubrovnik – who spent eight months in prison for the Sultan’s request to increase the annual tribute – meet with the new delegates Jakimir and Bunić. The Dubrovnik-Ottoman conflict is obviously over.

58The relation of the three thematic worlds (historical, romantic and eschatological) in Dionorić Palmotić’s epic is closer to the poetics of the Tassian epic than Gundulić’s Osman. Neither women warriors nor women diplomats appear in Dubrovnik Restored ; therefore there is no “danger” that male protagonists will enter into direct relationships with female romantic characters. The function of romantic episodes is taken over by two narrative digressions in two diplomatic journeys, both of which are set in the Ottoman Balkans. First, in the sixth canto of the epic, the Dubrovnik diplomatic representative traveling to the Bosnian Pasha witnesses the execution of a woman. He learns the whole story from a Bosnian Muslim friend : the woman named Fakre, driven by sexual lust, caused the death of her own husband and the man she pursued. In contrast to that somewhat misogynistic and dark digressive story, the second romantic episode is narrated in the present time of the narrative and has a happy ending (cantos IX–XI). Jakimir and Bunić, while on the way to the Sultan, encounter in a forest in southern Serbia three naked girls tied up. They are the daughters of the mufti of Sofia, who went with two brothers and three guards to visit their aunt in Niš. In the forest, they were attacked by highwaymen, who overpowered their brothers and killed the guards, tied the sisters up, and then launched an attack on some traveling merchants. The military escort of the Dubrovnik delegates free the girls, help their brothers to recover, bury the killed guards, and finally defeat the highwaymen. The episode ends with the return of the sisters and brothers to Sofia and the wedding of the oldest sister, which is attended by Dubrovnik diplomats as guests. The romantic episodes are separated from the main plot line and have a relaxing function in relation to the main theme of the epic.

-

26 Cf. Kravar, Zoran, Das Barock in der kroatischen Literatur, 142.

-

27 Stojan, Slavica, “Struktura i sadržajna koncepcija Palmotićeva spjeva”, 191.

59The place of eschatological episodes in the composition of the epic is also functional and logical. The forces of Heaven support Dubrovnik ; they act on a vertical axis : the hermit Pavo – Saint Blaise – God, and guarantee a happy future for Dubrovnik as early as the second canto of the epic. But the hellish forces as enemies of Dubrovnik are urging the Turkish side to seek an increased annual tribute just when things seem to be going well for Dubrovnik (cantos IV, XVI). Heaven reacts immediately (cantos V, XVII and XVIII) and takes the final victory (canto XIX). This view of the composition of the epic leaves the impression that the eschatological world determines the fate of the historical world (the romantic world in Dubrovnik Restored is free from heavenly/hellish influences). But is that correct ? Is the representation of historical events between the sixth and sixteenth cantos of the epic dependent on transcendent forces ? Zoran Kravar answers this question in the negative, arguing that eschatological episodes have an allegorical rather than causal relationship to historical events.26 It could be said that events in the eschatological world exculpate Ottoman politicians, but blame the Turkish/Islamic faith. Slavica Stojan considers that the indecorous scene with the Prophet Muhammad in Hell led to ignoring Dubrovnik Restored in its own cultural environment.27 Anyway, Palmotić Dionorić, like Gundulić, although the former skilfully follows Tasso’s poetics, gives preference to the historical world. His epic is a panegyric of sorts in praise of Dubrovnik diplomacy, and even his own diplomatic endeavor. However, the epic depiction of Dubrovnik’s diplomatic actions during the Great Earthquake is not idealized, Dubrovnik diplomats do not shy away from lies, duplicity and bribery.

60Earthquake and diplomacy are not common epic themes in seventeenth-century European literature. However, Jaketa Palmotić Dionorić had no other choice in the vernacular language, which at that time in the Dubrovnik culture was the language of fiction and everyday communication. The Dubrovnik poet and diplomat could write memoirs – the most appropriate genre for the subject matter of his epic – but only in Italian.

Petar Bogašinović’s Beča grada obkruženje

-

28 Cf. Fališevac, Dunja, “Opsada Beča g. 1683. u hrvatskoj epici (‘Obkruženje...

-

29 The literature also cites a third, posthumous edition, printed in Venice i...

61The epic of the Dubrovnik poet Petar Bogašinović (ca. 1625–1700) Beča grada obkruženje od cara Mehmeta i Kara-Mustafe velikoga vezijera (The Siege of Vienna by sultan Mehmed and Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa) occupies a low place on the aesthetic scale of Croatian literary historiography when it comes to the longer epic texts of the 17th century.28 It is, however, relevant here for several reasons : it depicts the events of the war, it was published immediately after the events presented, and its origin is closely related to the political context of the time. The first edition of Bogašinović’s epic poem on the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683 was published as early as 1684 in Linz ; the text was not divided into cantos and consisted only of 740 verses in the already common metrical form of octosyllabic quatrains in alternate rhyme (abab). The author then went on to describe the events of the Great Turkish War and the beginning of the Morean War, and as early as the following year he published the second, expanded edition in Padua, with three cantos and a total of 1,560 verses. Both editions are dedicated to a participant in the battle Petar Ricciardi, an Austrian general of Dubrovnik origin.29

-

30 Cf. Fališevac, Dunja, “Petar Bogašinović : Beča grada opkruženje…”, 352.

-

31 Fališevac, Dunja, “Petar Bogašinović : Beča grada opkruženje…”, 355–356.

62The first edition of the epic, consisting of the first canto of the second edition, is somewhat reminiscent of Karnarutić’s epic The Conquest of the Fortress of Szigetvár – with its theme (siege of the city/fortress), motifs (gathering of the army, crossing the river, sudden attack of Christian defenders on the vanguard of the Ottoman army) and traditional epic narrator. But the final version with two additional cantos is more similar in content and composition to Sasin’s Battles. Namely, Bogašinović, like Sasin, after describing one battle, continues to describe the subsequent events of the war, and in the third canto he moves from the battlefield in Central Europe (battles around Esztergom, Visegrád, Vác, Virovitica, Pest and Buda) to the battlefield in the Mediterranean (Venetian conquest of Santa Maura and Preveza). Unlike Gundulić, Zrinski and Palmotić Dionorić, Bogašinović does not follow Tassian poetics ; there is no romantic or eschatological world in the Siege of Vienna ; moreover, there are no quasi-historical characters in the epic.30 In the relatively short epic, Bogašinović included many historical figures (Kara Mustafa Pasha, Leopold I, John III Sobieski, Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, Sultan Mehmed IV, Maximilian II Emanuel, Charles V of Lorraine, Pope Innocent XI and others) and war events, so the Siege of Vienna as a chronicle in verse had a reporting/referential function for contemporaries and later readers – a large number of transcripts from the 18th century have been preserved.31

-

32 Dukić, Davor, Poetike hrvatske epike 18. stoljeća, Split, Književni krug, ...

63Does this mean that in Bogašinović’s epic, as in several previous epics, contemporary politics had emancipated itself as an autonomous field ? No. On the contrary, while Bogašinović’s narrator often comments on and contextualizes historical/political events, he always does it within the framework of Christian eschatology. The title character Kara Mustafa Pasha, who is indeed the main character of the first two cantos (until his death is detailed at the end of the second canto), is portrayed as the embodiment of the sin of pride, similar to and even more pronounced than Gundulić’s Osman ; in the speeches of prominent Christian figures the war is defined as a religious, rather than a political conflict ; God plays a decisive role in the victory of the Christian forces near Vienna (he sends the disease to the Turkish camp, destroys the Turkish trenches in the rain, and gives courage and strength to the Christian soldiers) ; the narrator most often compares the actors of contemporary events with biblical characters.32

-

33 A synthetic article about Petar Bogašinović and his epic, with special ref...

64Is therefore Bogašinović a conservative epic author, in a poetic and ideological sense ? Here, too, the answer is no. The Christian-theological framing of the Second Siege of Vienna and the events that followed it probably does not stem so much from the author’s conservatism as from the function of the literary text, and that function was distinctly political. Namely, Bogašinović’s epic is not only a versified account of war events but also a panegyric of some of its actors, first to the Austrian Emperor Leopold I, then to John III Sobieski and other defenders of Vienna. In August 1684, Dubrovnik signed a treaty according to which it returned under the protection of the Hungarian king and Habsburg emperor Leopold I, after two centuries of political dependence on the Ottoman Empire. The Siege of Vienna can thus be interpreted as part of the diplomatic efforts of the Dubrovnik Republic in the mid-1680s. The dedication to Petar Ricciardi and the praise to him and Frano Gundulić, the son of the author of Osman and a general of the Austrian army of Dubrovnik origin, are in line with this. It soon became clear that Dubrovnik’s diplomacy/government erred in its foreign policy assessment, as the Republic remained in the sphere of influence of the Ottoman Empire until the arrival of Napoleon’s troops in 1806, but nevertheless Bogašinović’s epic remained interesting to Dubrovnik readers for some time to come.33

A foundation epic on a grand scale : Petar Kanavelić’s Sveti Ivan biskup trogirski i kralj Koloman

65The poet and playwright Petar Kanavelić (sometimes called Kanavelović, 1637–1719) is the author of one of the most diverse in terms of genre and one of the most extensive literary works in Croatian early modern literature. Kanavelić published only a small part of his oeuvre during his lifetime, and his texts are preserved in numerous manuscripts scattered in a number of domestic and foreign libraries and archives. This is probably the main reason why the texts of one of the most important Croatian early modern writers are not published in a single critical edition (for example, in the edition “Stari pisci hrvatski”/“Old Croatian Writers”).

66On a political level, Kanavelić is a Dalmatian writer : his native speech was Chakavian, he was born on the island of Korčula, in the territory of the Venetian Republic, where he spent most of his life and where he died. However, his sense of belonging is not only related to Dalmatia, and Kanavelić is usually referred to as a Korčula-Dubrovnik writer. He was connected to Dubrovnik by friendly and family ties : he was a member of the Dubrovnik “Academia otiosorum eruditorum”, both his wives were from Dubrovnik and, perhaps most importantly, he wrote in the Dubrovnik literary idiom. Given the subject of this article, it is important to note that Kanavelić is the author of several occasional poems (although not epic poems in the narrow sense of the word) about contemporary political events : the Great Earthquake in Dubrovnik in 1667 (Grad Dubrovnik vlastelom u trešnji/The City of Dubrovnik to Noblemen in Earthquake), the execution of Petar Zrinski in 1671 (Dođi, o ljubi mâ ljubjena/Come, O my dear beloved !), the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683. About the latter event Kanavelić wrote two poems in praise of John III Sobieski (Pjesan u pohvalu privedroga Ivana Sobjeskoga, kralja poljačkoga/The Poem in Praise of Glorious John Sobieski, the King of Poland ; Pjesan u pohvalu kralja poljačkoga/The Poem in Praise of the King of Poland). The same event prompted Kanavelić to write an epic about the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha (Kara Mustafa vezijer Azem/The Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa), but he abandoned that plan only eight stanzas into the first canto. Kanavelić still managed to write an extensive historical epic, and the last work in his oeuvre : Sveti Ivan biskup trogirski i kralj Koloman (Saint John Bishop of Trogir and King Coloman). Although the epic was actually written in the 18th century, between 1705 and 1718, it is the last text of the Croatian Baroque historical epic, and as such an example of a genre more characteristic of seventeenth-century Croatian literature, and thus deserves a place in our study.

67Kanavelić’s epic is the most extensive text in that corpus : it includes 24 cantos for a total of 19,084 verses arranged in quatrains in alternate rhyme (abab). The historical subject of the epic is the conquest of Dalmatian cities by the Hungarian king Coloman at the beginning of the 12th century, making Kanavelić the only Croatian epic poet to have taken up Torquato Tasso’s poetic invitation to consider the Middle Ages as the ideal time setting of the historical epic. Besides, Kanavelić followed Tasso better than his Croatian predecessors in integrating the romantic world into the whole epic story. Romantic episodes with female characters on the battlefield, identity changes, love stories, journeys to exotic lands and the like, are evenly distributed throughout the epic and do not jeopardize the basic historical story.

68Kanavelić’s epic has two main (title) characters, one an actor in political history (King Coloman), and the other an actor in sacred Christian history (Bishop Ivan of Trogir, historical Giovanni Ursini, later the patron of the city of Trogir). That is why the traditional eschatological world of Baroque epic is almost completely absent from Kanavelić’s epic (namely, heavenly and hellish characters and settings). The forces of Hell appear only in the 21st and 22nd cantos, and the last five cantos thematize events after the Saint’s death, i.e. his miracles, which brings this part of the epic closer to hagiography. The function of the eschatological world is in the rest of the epic taken over by Saint John of Trogir, so that world ultimately dominates the text. The typical plot of the Baroque historical epic – the struggle between two warring parties permeated with romantic episodes (albeit without the interference of heavenly and infernal forces) – ends as early as the 13th canto. In the next six cantos (XIV–XIX) the destinies of romantic characters are resolved and the new order in Dalmatia is strengthened : the Dalmatian cities accept the Hungarian king Coloman as new ruler, and he guarantees Dalmatians their autonomous rights. In particular, Saint John achieves a compromise solution : he prevents Coloman’s conquest of Zadar and thus ends the Christian-Christian conflict, but immediately afterwards enables the Hungarian king to take power in Dalmatia peacefully and by agreement. Coloman, an arrogant and aggressive king in the first part of the epic (cantos I–XIII) is transformed in the middle of the epic (definitely in canto XVII), by the action of St. John, into a peaceful, responsible and tolerant ruler.

-

34 The following facts on the interest in the life and character of Bishop Iv...

-

35 Zlata Bojović gives a negative answer to that question, and Miljenko Foret...